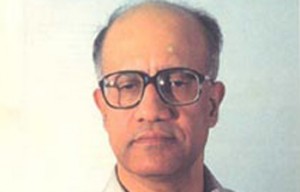

For approximately 25 years, a pediatrician wrote and sent postcards to the poor to guide them on preventing and treating of diseases as a teenager, a poor villager in Andhra Pradesh wanted to join the postal service. With no money for higher education, a job with the government agency could have made his life secure.

But a relative supported him financially and sent him to medical school. That changed the life of Araveeti Ramayogaiah, who later went on to become a pediatrician. Decades later, his day-to-day practice became inseparable from the postal service.

Photo: Rahul M/qz.com

For almost 25 years, Ramayogaiah wrote and sent postcards to India’s poor, especially women, telling them about ways to prevent – rather than cure – diseases. The good doctor died in Hyderabad in September this year at the age of 65. The inexpensive postcard was Ramayogaiah’s solution to private hospitals, which are typically inaccessible and unaffordable for many of India’s poor.

In all, he wrote around 36,000 postcards to patients, acquaintances and strangers – explaining basic habits like boiling water and washing hands, and how to prevent commonplace diseases like diarrhoea.

“Eighty percent of diseases in India are waterborne and airborne, and can be easily prevented,” Ramayogaiah told Rahul M, a freelance journalist, earlier this year. “All that one needs to do is have clean surroundings and drink boiled water.”

Ramayogaiah emphasised on “preventive aspects rather than curative,” said Rama Devi, who works at Jana Vignana Vedika, an organisation working for the popularisation of science, in Andhra Pradesh. She is also a doctor at Gandhi Medical College and Hospital in Hyderabad.

Postcard movement/scroll.in

“He often joked that if doctors in India were to go on trike for 10-15 days, the mortality rate during that period would decrease because doctors wouldn’t be writing prescriptions,” she said. “He would say doctors are creating iatrogenic (caused by treatment) diseases. First they give medicines, that causes side-effects, so more medicines…and that’s a vicious cycle.”

In a column especially for THE HINDU newspaper, in the year 2011, Ramayogaiah wrote:

We, doctors, know for sure from our long years of gruelling studies that most of the symptoms are self-limiting, most others are trivial and very few are serious. In the name of evidence-based medicine and defensive medicine, we order a battery of investigations even for trivial symptoms… Unnecessary tests are a loathsome burden on patients and, at times, result in false positive results leading to unscientific treatment.

“Health is to do with water, nutrition, environment and good sanitation,” Devi stated. “Doctors come into picture when a disease takes place. So why do people say that doctors give health, he would say.”

From 1990 till 1998, Ramayogaiah worked in the pediatric ward of Chittoor’s Government Headquarters Hospital, from where he wrote his first postcard.

At the hospital, he was also connected to the Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India, an initiative to encourage women to breastfeed infants. Roughly 2,500 women used to deliver babies every month, and typically, they would return to their homes in the nearby villages after the delivery.

Image: Financial Express

“He started thinking how do we know whether the child was getting vaccinated properly, and according to the date,” A Naga Sujana, Ramayogaiah’s daughter, said. Eventually, he decided to collect the addresses of these new mothers from the hospital’s gynecology department and write to them directly.

“So in a postcard, he would list all the vaccinations, the dates when they were due, and at what age of the child,” Sujana recalled. “He would then sign it with a ‘wishing you good health’ and post it.”

The doctor also ensured the postcards were sent from the hospital he worked at. “That way, when women receive these postcards, they would take them seriously as they look official,” Ramayogaiah, said in an interview, earlier this year.

His idea worked immediately. Women would often return to the hospital for the vaccinations and profusely thank him. “These were mostly uneducated women. So the postmaster who would be delivering the letter would read them aloud for them,” Sujana said. “At that time, he sent some 1,500 postcards.”

During his next posting, in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, he sent out another 2,500 postcards on polio vaccination. “He had fallen very sick, and he could not participate in the Pulse Polio campaign, so he wrote postcards and sent them to villages,” his daughter recalled. Pulse Polio is an immunisation programme by the Indian government to eliminate polio. In 1995, the campaign was scaled up to cover all of India’s population.

Source: Scroll.in

Tags: Araveeti Ramayogaiah Dr. Araveeti Ramayogaiah