Director: Kelly Reichardt

Writers: Maile Meloy (short stories), Kelly Reichardt

Stars: Laura Dern, Michelle Williams, Kristen Stewart

Based on Maile Meloy’s collection of short stories, Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It, Kelly Reichardt brings for the audience a dispersed portrayal of a series of vignettes spun around ‘certain women’. The movie in itself isn’t trying to tell a story but does so elegantly by letting the viewer compose a thread to infuse into and weave through it. The canvas chosen by the director is right up in her alley which reminds of her previous venture, Meek’s Cutoff, in terms of quiet filmmaking. With drops of feminist angles, although a bit juvenile, drizzled all over the plate, Kelly Reichardt erects her characters in beds of mundane struggles. Amidst a plethora of blockbusters with their loudness and penchant for fantastical scopes, Kelly Reichardt pursues a glance at life in its unapologetic ordinariness through elliptical narratives.

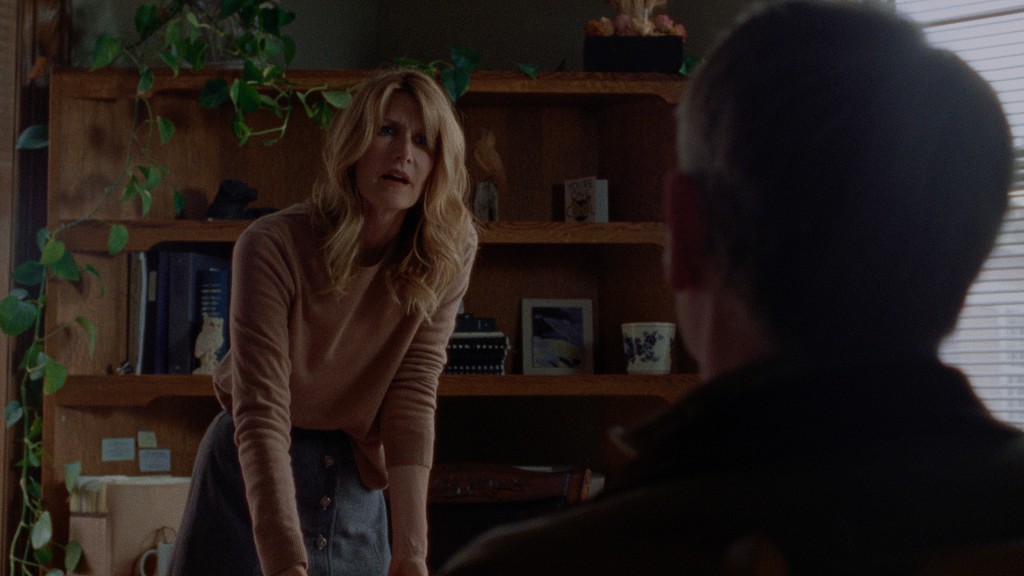

The movie is a superficial broad-stroke that elicits the lives of three independent women. Set against the backdrop of hauntingly silent Montana, three women find themselves in a meaningless existence, only to fight suffocation with resilience. Reichardt’s acute observation of the daily lives finds its focus, at first, in a small town lawyer, Laura Wells (Laura Dern). The character tackles an injured laborer named Mr. Fuller (Jared Harris) who embodies the same helplessness that is glaring throughout the movie. Human connection is fabricated and the reality seems to be a bleak shadow in the fleeting monotony of Laura’s life, where she is interrupted in her adulterous hookup and in turn becomes the unwilling epicenter of Mr. Fuller’s weary attempts at creating a connection. Laura’s advices are shrugged off by Fuller, only to be accepted when offered by a man and thus she is left uttering, “if I were a man I could explain the law and people would say ‘OK’. It would be so restful.” The lives are encountered with an authoritative silence as rejection abounds for Fuller from an emotional and survival standpoint. Laura’s befuddlement is handled by Reichardt with a chilling nonchalance that mocks the gravity of a hostage situation itself and poses a question as to how futile a personal struggle is in a potential dystopia.

Reichardt plays with the coincidences of the modern trend, the ‘shared universe’, and presents an antithesis of it by connecting three splintered yet homonymous narratives in a lack of hyperlinked setup. This is achieved with minute detailing of the situations and the controlled overlapping of characters. As the movie phases forward, a couple is introduced to the viewers. Gina, played by Reichardt frequent Michelle Williams, and Ryan (James LeGros) are upheld in a visual barrenness where Christopher Blauvelt’s cinematography amplifies the worn out relationship. A placid peak into senility is explored through the character of Albert (René Auberjonois), who is approached by the couple for some sandstone. The motivation of building a house is subtly coupled with the decaying of a life amidst the wilderness where silence smothers the expectations of human bonding. The couple is shown to be in a marital struggle and their sullen daughter is caught up in a drama that doesn’t fully play out, thus feeding the incompleteness of life. Williams is seen to be in her element, be it in a desolate walk or a disappearing smile. The frustration with life internalized in Gina is what binds her with the other ‘women’.

The thread of nothingness is knit with a tangential sneak into the only fulfilling narrative which features a ranch hand named Jamie (Lily Gladstone). While Laura and Gina possess an aura of detachment, Jamie brings about the opposite facet with a yearning for a law graduate, Beth (Kristen Stewart). In an extension of the monotony, Reichardt sets her third focus in a world of silent relationship with horses, a bond that is groped at with an awkward tenderness in the case of Beth, only to be rejected. Jamie is portrayed in a gentle whirlwind where she stumbles upon Beth after attending a class, having nothing else to do. The narrative eases into a conversation and just when an atmosphere of emotional padlock seems to be appearing in a distance, Reichardt jolts and lulls the viewer, simultaneously, into the previous rhythm. Gladstone convincingly brings to screen the heartbreak and the inevitable negotiation with rejection while driving back after meeting Beth.

In a cruel sweep, the women are brought into a panorama of silent agreement with life. Silence prevails throughout the movie and quietly gets wrapped up through Laura’s acceptance of Fuller’s puerile indulgence to Gina’s meshing with the promise of stability and finally, Jamie’s falling back to the life where she has no agency.

The movie leaves an unsettling impression where the three women are rendered as brushes to actually portray the mundane small town. Like life, the movie ends without any answer to the dilemmas and struggles faced by the characters, which align perfectly with Reichardt’s personal style. In a theatrical gallery of composite sketches and formulaic storytelling, CERTAIN WOMEN brings a numbing sensation of the unknown and leaves with an itch that resembles the anxiety and relief in the last thought of a night. While it is a genuine feat of filmmaking, the movie falls short of the modern demand of pace and creates an anathema for people who crave a conclusion.

Review by Agnimitra Roy

My Verdict

My Ratings

3.5

Like life, the movie ends without any answer to the dilemmas and struggles faced by the characters, which align perfectly with Reichardt’s personal style.